The Beach (2000), directed by Danny Boyle and based on Alex Garland’s novel, explores several deep and sometimes conflicting themes.

While it might appear on the surface as a backpacker’s paradise-gone-wrong story, it’s really a layered reflection on human nature, idealism, and the dual nature of reality.

A few words on The Beach

Alex Garland, known for directing Ex Machina and Civil War, is also the author of the novel The Beach. The film adaptation was directed by Danny Boyle, acclaimed for Trainspotting and Slumdog Millionaire.

Interestingly, Garland and Boyle later collaborated on several projects, including Sunshine, 28 Days Later, and its upcoming sequel 28 Years Later.

The themes

1. Identity is the Choices we Make

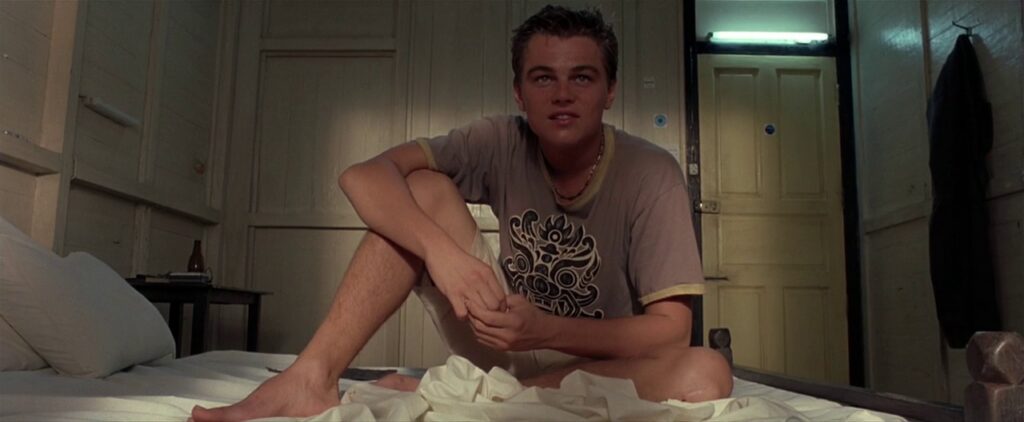

All we initially know about Richard is that he has an American accent — and that’s no accident. His past, family, and background are left in the shadows because they don’t matter in the world he’s about to enter.

In The Beach, identity isn’t tied to biography but to choice — the adventure one dares to live. What defines Richard is not where he comes from, but what he’s searching for: a break from the scripted, a confrontation with something real.

2. A Universal Search for Authenticity

When Richard arrives in Bangkok — the Western gateway to Southeast Asia — he steps into a mirage. The city is draped in exoticism but underneath lies the same consumerist rot, just dressed differently. Daffy’s rant about “wankers” isn’t just cynical; it’s a warning. Tourists play at rebellion while staying firmly inside the safe bounds of culture-as-commodity.

But Richard, like Daffy once did, believes he’s chasing something purer: a life untouched by simulation. He seeks the raw, the dangerous, the meaningful — something outside the frame of Western life and its endless performance. It’s not about escape for pleasure, but escape for truth and authenticity.

3. The Call to Adventure

Daffy gives the map to Richard, I believe, because he sees in him more than just another aimless tourist chasing cheap thrills. Richard isn’t performing or trying to impress — he’s present, honest, and open in a way that cuts through the noise. In their brief exchange, Daffy senses a rare authenticity: Richard listens without judgment and speaks without pretense.

He’s not there to consume an experience, but to feel something real. That sincerity, that quiet hunger for truth, is what Daffy refers to when he talks about people with an ideal. It’s those who still believe in something deeper, even if they can’t fully articulate it, who are both drawn to — and destined to be changed by — the island.

Although Daffy appears to have lost his grip on reality, he still serves as a kind of twisted mentor — delivering truths, albeit in a distorted and extreme form. Daffy is actually the only one who sees the big picture at this moment.

4. The Human Fear of Being Alone

Richard’s journey is deeply existential, but it’s not one he wants to face alone. Despite craving detachment from the world, he’s still tethered by his humanity — his need for connection, recognition, and witness. That’s why he invites Françoise and Etienne. Not just for companionship, but to reflect and validate the meaning of the path he’s chosen.

Later, when he shares the map with two strangers, it’s not just recklessness — it’s a moment of human contradiction. The desire to keep paradise pure collides with the fear of solitude. In chasing an ideal, he still wants to be seen doing it. He wants to disappear from the world… but not without leaving a trace.

5. The Beach as Myth and Paradise

The Beach is both myth and paradise — myth, because it represents the timeless fantasy of an untouched utopia beyond society’s grasp; paradise, because for a fleeting moment, it delivers exactly that.

On the island, the characters become creators. There are no titles, schedules, or commands. No offices, lines, or obligations. In nature, they shape their days with instinct, sun, and salt — a life built by hand, not by system.

It’s the dream of radical freedom: a communal life unchained from capitalism and performances. But like all myths, paradise collapses once it’s possessed. The more they try to preserve it, the more rules, borders, and exclusions arise. In protecting the ideal, they destroy it.

The Beach shows that you can’t escape society by leaving it — because the very flaws of society live within us. Wherever we go, we bring ourselves.

6. The Island a Mirror of Civilization

The society on the island in The Beach is surprisingly organized — and that’s what makes its eventual collapse so revealing. Despite being formed by people who wanted to escape the constraints of civilization, the community recreates many of its same structures, just with a new aesthetic.

There are unspoken hierarchies: Sal, the de facto leader, makes decisions and enforces order, even manipulating others to maintain control. There are designated roles — some fish, others cook, build infrastructures, or fix things. Tasks are divided, and everyone is expected to contribute. They hold meetings, resolve disputes, and even celebrate events together. On the surface, it seems harmonious — a micro-society running smoothly without external governance.

But beneath the surface, this structure masks deeper tensions. The more they try to preserve paradise, the more they start building walls — not physical ones, but psychological. Outsiders are excluded. External trips are forbidden. Rules tighten. Secrets grow. Power becomes concentrated in subtle ways. Dissent becomes dangerous. Their organization, once a symbol of unity, turns into a mechanism for control and denial.

Ironically, their attempt to live freely ends up mirroring the very systems they tried to escape — proving that human nature tends to recreate order, and that any society, no matter how small or idealistic, is vulnerable to the same patterns of corruption, fear, and self-preservation.

7. The true masters of the place

The farmers in The Beach represent the harsh boundary between illusion and reality. While the island community indulges in their dream of paradise, the farmers are a constant, looming reminder that this dream exists within someone else’s land — and at their mercy. They are not part of the fantasy, nor do they care for it.

Their presence is raw, grounded, and territorial, embodying a reality that the beach dwellers choose to ignore. In a way, the farmers symbolize the real world pushing back against the delusion of utopia. They are not villains — they’re simply protectors of their world, one that doesn’t allow for outsiders playing at freedom without consequences.

The only reason they are tolerated is that the illegal trade makes it difficult to expel them quietly.

8. Seekers vs. Tourists

In The Beach, Richard, Étienne, and Françoise are accepted into the island community because they carry the quiet, introspective energy of seekers — open, respectful, and sincere — while the other tourists (Zeph, Sammy, and their friends) represent loud, shallow consumption of wankers.

Richard’s trio arrives humbly, wanting to experience something real, whereas the others symbolize mass tourism, bringing with them noise, entitlement, and the threat of exposure. It’s not just about numbers — it’s about vibe. The island functions on a delicate balance, and Daffy’s initial choice of Richard marks him as someone different, someone still holding an ideal.

The rejection of the others isn’t personal; it’s symbolic. They represent the outside world, and the community’s fear isn’t just of people — it’s of losing the illusion of paradise itself.

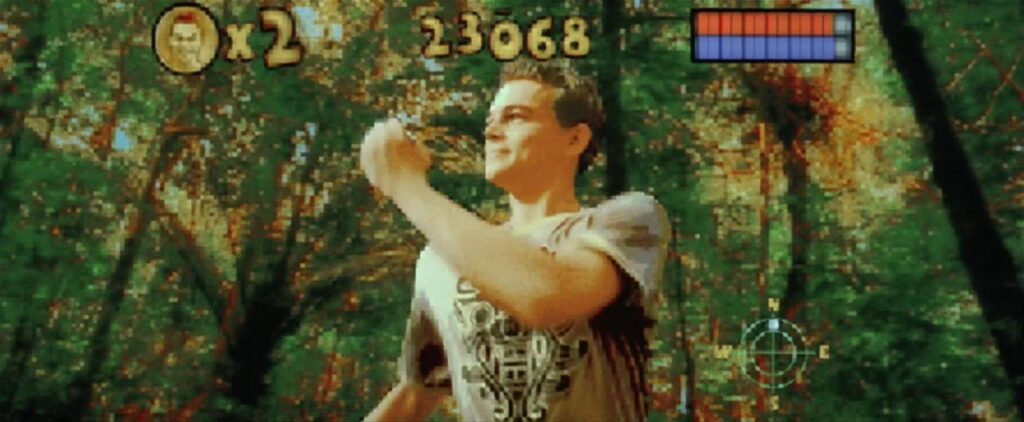

9. The Video Game Episode

The island, once seen as a utopia, slowly reveals itself as a fragile illusion — the same destructive patterns of the outside world resurface, especially after the shark attack.

As tensions rise and the outsiders are seen near the island with a map, Richard is forced to confront the consequences of his choices and retreat into isolation.

The video game sequence and Richard’s descent into madness illustrate how individuals construct internal narratives to navigate between identity and chaos. But when these narratives go unchallenged — in the absence of a stable community — they can spiral into dangerous delusions.

It’s then that reality begins to slip — becoming elusive, detached, and nearly impossible to grasp alone. Even we, the viewers, lose our grip on what’s real and what’s not. What follows strongly echoes Colonel Kurtz’s fall in Apocalypse Now, a madness already foreshadowed at the start of the film. Perhaps humans are not made for truth, but for collective illusions that preserve their sanity and connection to the world.

10. The Final Cyber Space Scene

In the final scene, Richard sits in a cyber café, surrounded by people glued to their screens — passive, plugged-in, and distant. His expression isn’t just bored — it’s alienated. After what he’s lived, this world feels sterile, like a plastic echo of real life (Simulacra and Simulation).

But when he sees the photo of the island, something softens. His smile isn’t just nostalgia — it’s recognition. The beach is gone, but it was real, and it mattered. It shaped him. It scarred him. And that scar is sacred.

He doesn’t return to society enlightened, but marked. He’s not trying to recreate the illusion — he carries the truth quietly, as a memory, an anchor. Something to remind him that for a moment, he touched something that cut through the noise.

11. Was Life on the Beach Real or Just Another Illusion?

What is reality? Is it the system we’re born into — the routines, laws, and expectations society constructs for us? Or is it something deeper, something primal that lives beyond language, beyond architecture and money, beyond the curated paths we’re told to follow?

In The Beach, reality is questioned from the very start. Richard flees a world of schedules and fluorescent lights, where reality feels synthetic — like a simulation made of noise, distraction, and shallow pleasures. Bangkok, at first glance, seems like an escape. But it’s still part of the machine — a tourist façade offering exoticism without authenticity, consumption disguised as adventure.

The island, then, becomes the battleground for the question: Is reality what society says it is, or what you experience when all those systems fall away?

On the island, there are no institutions, no brands, no clocks. Just people, nature, instinct. It feels more real than anything Richard has known — because it strips life down to its core: survival, community, desire, fear, beauty, chaos. There, people build a new world, guided not by social rules but by necessity, emotion, and vision. For a while, it worked — until their human flaws inevitably seep back in: control, exclusion, power, denial.

So is that reality? A raw, unfiltered mirror of human nature?

The Beach suggests that reality isn’t defined by society, or even by consensus. It’s defined by what transforms you. The beach was “real” not because it lasted, but because it broke Richard open. It stripped away everything artificial until he stood face-to-face with the truth — about himself, about others, about paradise. In contrast, the world he returns to — with its screens, distractions, and empty interactions — seems less real than ever.

In the end, The Beach doesn’t give a single answer. Instead, it whispers:

Reality might not be what surrounds us. It’s what wakes us up.

When we confront raw reality, we face ourselves, without masks or compromises, which can allow for a form of reconciliation with our true being.

And if you have the luck to be surrounded by people sharing this authenticity and a common ideal, that’s where paradise can exist briefly in a parallel universe.

Conclusion

The Beach might, on the surface, seem like a stylish adventure for young backpackers — a cinematic escape into turquoise waters, exotic landscapes, and youthful rebellion. But beneath that tropical postcard lies something far deeper and more unsettling. The film poses profound questions about the structures of civilization: how we cannot help but rebuild the very systems we claim to flee, how every utopia is built on rules and exclusion, and how paradise turns to nightmare the moment we try to possess it.

It explores the illusion of freedom, the tension between individual desire and collective order, and how even in the wild, human nature craves control, belonging, and hierarchy. The descent into madness is not a break from reality — it isreality, laid bare, stripped of comfort and distraction.

And yet, amid the collapse, there’s growth. Not the triumphant kind, but the painful, irreversible kind that marks a soul forever. In the end, The Beach reveals that the true adventure is not the place, but the journey — the choices, the losses, the revelations.

It’s not about finding paradise, but about what we experience and become in the search — and the authentic connections that the journey brings to life.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings