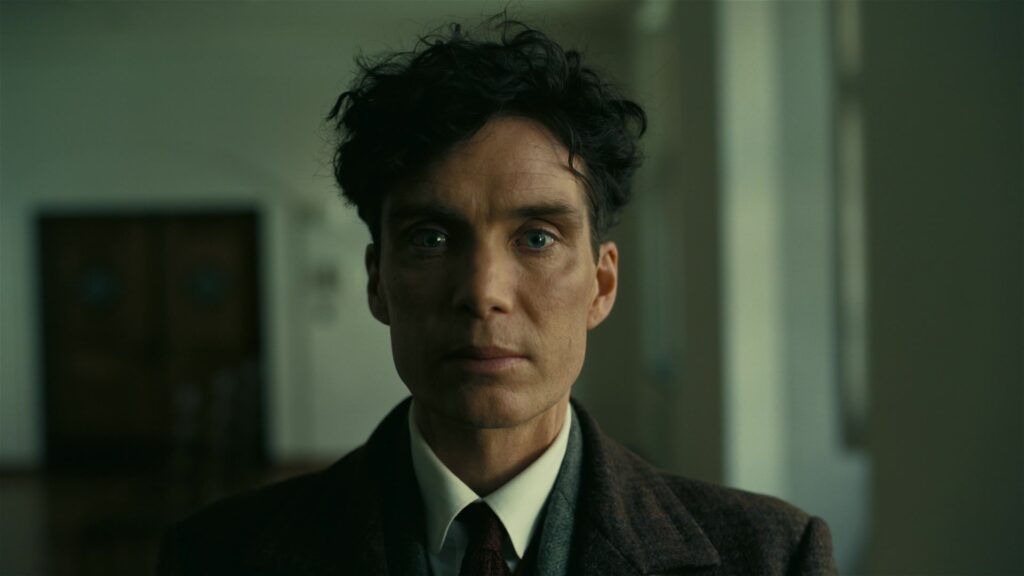

In the movie Oppenheimer, the question “Can You Hear the Music?” which also serves as one title of the original soundtrack, acts as a metaphor that is gradually unveiled throughout the story.

The film uses this metaphor to question the very concept of what it means to be a human and perhaps a true protagonist. In this article we will delve into why this metaphoric question is perhaps one of the most important you can ask yourself.

Note: This article focuses solely on analyzing characters from Christopher Nolan’s 2023 film.

What is a protagonist?

A protagonist is the main character in a story, play, movie, or other narrative work. This character is often the one the audience follows most closely and typically faces challenges, obstacles, or conflicts that drive the plot.

The protagonist is usually central to the story’s theme and the one whose actions and decisions shape the course of events. In many cases, the protagonist undergoes personal growth or change as a result of the journey or experiences they face.

The moral arc of protagonists

The protagonist in a story often explores moral questions and ethical dilemmas, driving the narrative through their actions and decisions. Their journey typically involves a conflict between competing values, which shapes their character development.

Protagonists frequently confront dilemmas involving good vs. evil, selflessness vs. selfishness, or personal gain vs. the greater good. How they navigate these challenges reveals the ethical themes of the story, leading to personal transformation or tragic outcomes.

The moral arc of the protagonist often reflects the story’s central message, whether it’s about virtues like honesty or the consequences of moral failure. Modern protagonists are often complex and flawed, making their moral choices more nuanced and inviting audiences to reflect on their own ethical beliefs. They still act according to a value system focused on collective well-being and selflessness.

What is an antagonist?

An antagonist is a character or force in a story that opposes or creates conflict for the protagonist, who is the main character.

The antagonist is often seen as the “villain” or adversary, but it can also be a non-human force, such as society, nature, or an internal struggle within the protagonist. The role of the antagonist is to challenge the protagonist, creating obstacles and driving the narrative conflict.

The moral arc of antagonists

The moral arc of an antagonist refers to their ethical journey throughout a story. Often, antagonists begin with noble intentions but become corrupted or misguided by power, desire, or a flawed sense of justice, showing how circumstances can lead someone away from morality.

In some stories, the antagonist represents a direct moral opposition to the protagonist. Their unwavering commitment to an opposing ideology or belief creates conflict, with their actions often challenging the protagonist’s values.

An antagonist who embraces rationality, hedonism, nihilism, immorality, or the will to power will eventually reveal four key dark and selfish traits. First, manipulation of others for personal gain, disregarding the welfare of those around them.

Second, self-interest that prioritizes their desires and goals, often at the expense of others’ needs or rights. Third, disregard for morality, choosing actions that harm others without concern for ethical consequences.

Finally, a desire for control, driven by the belief that power and dominance are the ultimate measures of success. These traits highlight the antagonist’s descent into selfishness and their moral conflict with the protagonist.

What does Can You Hear The Music Really Means?

Niels Bohr: Algebra’s like sheet music, the important thing isn’t can you read music, it’s can you hear it. Can you hear the music, Robert?

J. Robert Oppenheimer: Yes, I can.

In Oppenheimer, when Borg asks him, “Can you hear the music?” it’s a metaphorical moment that reflects the tension within Oppenheimer’s character. At this point in the film, Oppenheimer struggles with the ethical and emotional weight of the power and responsibilities of understanding quantum mechanics and his future involvement in the creation of the atomic bomb.

Borg’s question serves as a subtle probe into Oppenheimer’s conscience, questioning whether he can truly understand or feel the gravity of the consequences of his actions. It symbolizes the dissonance between scientific achievement and the moral and human cost that comes with it, urging Oppenheimer—and the audience—to confront the deeper implications of his work.

Can you feel the emotion?

Beyond the technicalities of science or history, do you connect with the human experience—the triumph, guilt, and sorrow of those involved?

Can you sense the morality?

Do you perceive the weight of the ethical dilemmas, the consequences of actions, and the profound moral ambiguity of decisions like creating the atomic bomb?

Can you grasp the universal existential depth?

Are you attuned to the deeper questions about humanity’s place in the universe, our capacity for creation and destruction, and what it means to wield such immense power?

To hear the music is to move beyond the surface—to feel the resonance of the film’s themes in your heart, soul, and conscience. It’s not just about understanding; it’s about experiencing and reflecting.

Why might Oppenheimer be seen as a protagonist, despite his role in creating a weapon of mass destruction?

Oppenheimer may be seen as a protagonist despite creating a weapon of mass destruction because his character embodies moral conflict, responsibility, and the pursuit of knowledge. Driven by a sense of duty during a global conflict, he faced the tension between scientific advancement and its potential harm.

His internal struggle and the consequences of his work highlight the moral ambiguity of his choices, with his intentions aimed at racing the axis forces, ending war and preventing worse outcomes. This duality compels viewers to reflect on the nature of morality, human ambition, and the personal cost of progress.

Why is “Can you hear the music?” the most crucial question for humanity?

This question is essentially : Do you believe in God, do you have faith in the divine and the greater good?

It’s an existential question—can we, as a species, balance our thirst for knowledge, power, and progress with the awareness of the impact on life and the world around us? The “music” is a metaphor for that deeper understanding and empathy, asking whether we can hear, acknowledge, and feel the implications of our actions in a world where technology and progress can easily overshadow human values.

In this sense, the question is essential for humanity because it forces us to confront the larger ethical and philosophical dilemmas of our time, challenging us to listen to the “music” of compassion, responsibility, and awareness in the face of our growing power.

Someone who can read and create music won’t necessarily use it for noble purposes. For instance, some may create music to generate wealth, gain fame, or manipulate others such as promoting hedonism.

Melody and Harmony in Music, Art and Religion

Melody and harmony are key to music, providing depth, emotion, and structure far beyond isolated notes. While individual notes hold significance, it is their combination into melodies and harmonies that creates true expression.

Melody creates continuity and narrative, while harmony adds richness and complexity. Together, they form a unified musical experience that resonates emotionally, offering coherence and depth that single notes cannot. Without them, music would lack the emotional and relational power that makes it such a profound medium.

The Woman Sitting with Folded Arms 1937 by Pablo Picasso

Femme assise aux bras croisés (Woman Sitting with Folded Arms), painted by Pablo Picasso in 1937, is an important example of his later work, capturing complex emotional states through his characteristic style. The painting is often interpreted as a reflection of psychological and emotional tension, aligning with the broader themes of his work during the late 1930s.

Key Elements

1. Posture and Expression

The subject of the painting, a woman sitting with her arms crossed defensively, presents an image of emotional withdrawal. Her arms are tightly folded, creating a barrier between her and the outside world. The downturned gaze and somewhat somber expression suggest feelings of sadness, resignation, or perhaps deep contemplation. Her body language conveys a sense of emotional containment or vulnerability, suggesting that she may be retreating from the world around her.

2. Emotional and Psychological Depth

Picasso’s use of the woman’s posture and facial expression communicates an internal struggle. She is not simply passively sitting; her pose reflects an emotional state—perhaps frustration, alienation, or sorrow. The crossed arms, a common gesture in the human body language lexicon, symbolize emotional defense or withdrawal. In the context of the tumultuous 1930s, this could also reflect the artist’s awareness of the political and social unrest of the time, as well as personal experiences of loss and suffering.

3. Color Palette

Picasso’s use of muted tones in this painting, dominated by earthy colors like brown, yellow, and ochre, reinforces the somber mood of the piece. These colors, along with the woman’s closed posture, contribute to a feeling of heaviness or emotional confinement. There is a sense of emotional stillness, echoing themes of isolation or entrapment.

4. Context

Created in 1937, a time when Picasso was profoundly impacted by political events such as the Spanish Civil War and the rise of fascism, the painting can be interpreted as a symbolic reflection of the personal and political turmoil of the time. Picasso’s works from this period often grapple with themes of suffering, loss, and the human condition, influenced by both his own life and the larger social and political climate.

5. Psychological Realism and Formalism

While Picasso’s style evolves throughout his career, Femme assise aux bras croisés represents a convergence of psychological realism and formal abstraction. The emotional intensity of the subject contrasts with the more abstract and flattened composition, where the woman’s form is simplified, yet her emotional depth remains palpable.

Interpretations

Isolation and Resignation

The woman’s closed posture, combined with the heavy, muted color palette, evokes feelings of isolation, grief, or resignation. The figure’s withdrawal may reflect the broader human experience of detachment in a world fraught with conflict and uncertainty, mirroring the artist’s own sense of social and political alienation during a period of intense upheaval.

The Emotional State of the Artist

The painting’s mood can also be seen as an expression of Picasso’s own emotional state at the time, reflecting his struggles with personal relationships, political turmoil, and the broader sense of despair surrounding the Spanish Civil War and the rise of fascism.

Conclusion

Femme assise aux bras croisés is a powerful psychological portrait that encapsulates a complex range of emotions—alienation, sadness, and emotional conflict. Picasso’s minimalist yet expressive style, combined with the subject’s vulnerable posture, invites viewers to reflect on the broader human condition, especially in the context of societal upheaval. Through this work, Picasso creates a poignant representation of human suffering and introspection, urging viewers to engage with the emotional and political struggles of the time.

The Waste by T.S. Eliot

The Waste Land is a landmark poem in modern literature, written by T.S. Eliot and published in 1922. Widely regarded as one of the most significant works of the 20th century, it reflects the cultural, social, and spiritual anxieties of its time, particularly those arising from the aftermath of World War I.

The poem is dense, complex, and rich with literary, historical, mythological, and religious allusions. It is divided into five main sections:

- The Burial of the Dead

- A Game of Chess

- The Fire Sermon

- Death by Water

- What the Thunder Said

Key Themes

• Decay and Despair: Eliot portrays a modern world that is fragmented, disenchanted, and spiritually barren.

• The Search for Meaning: The poem explores humanity’s attempt to find purpose and significance in a shattered post-war landscape.

• Renewal and Redemption: Despite its somber tone, The Waste Land contains motifs of renewal, drawing on fertility myths and religious texts for potential hope.

The poem employs modernist techniques, including juxtaposition, abrupt shifts in perspective, and a fragmented structure, mirroring the disorientation of the modern world. It incorporates multiple languages (English, German, French, Italian, Sanskrit, etc.), reflecting its broad cultural scope.

The poem concludes with the famous line “Shantih shantih shantih,” a Sanskrit phrase from Hinduism meaning “the peace which passeth understanding,” offering a glimmer of hope in an otherwise deeply troubled text.

The Spiritual World

What if the spiritual world is not some distant, ethereal realm, but rather our capacity to map and understand existence? Perhaps the material world, with its tangible form and structure, serves as a reflection of this invisible spiritual realm—a realm constructed from patterns, rhythms, and harmonies that govern our experiences.

In this view, the spiritual world could be seen as the framework through which we perceive and interpret the physical world, guiding us toward deeper meaning and interconnectedness. Just as music relies on patterns of melody and harmony to evoke emotion, our spiritual awareness may use these same principles to help us navigate the complexities of life, creating a more harmonious experience of existence.

The visible world would then be a manifestation of these invisible spiritual patterns, with each moment offering an opportunity to align with a greater, universal order.

The meaning of life

The meaning of life can be viewed through two contrasting perspectives: one guided by a divine purpose, seeking goodness and a higher plan, and the other shaped by self-interest, power, and rebellion, reflecting the influence of the devil. Each path offers a unique interpretation of meaning, leading individuals on different journeys.

For protagonists: embracing suffering and the noble journey of responsibility and creation

The journey of finding meaning through suffering and maintaining nobility in responsibilities mirrors the story of Jesus Christ. His life and sacrifice exemplify enduring suffering with dignity and fulfilling his responsibility to humanity, despite immense hardship.

Jesus’ suffering, both physical and spiritual, demonstrated love, sacrifice, and forgiveness, transforming pain into redemption. Similarly, the pursuit of meaning often involves confronting suffering with grace, using it for personal growth. Like Jesus, we are called to embrace responsibility, face hardship with courage, and transform suffering into purpose.

For antagonists : the empty and self-destructive quest of power and pleasure

For antagonists, the meaning of life often revolves around personal power, self-interest, or nihilism, rejecting conventional morality. They may see suffering as a necessary part of life and use it to further their own desires, viewing control and manipulation as central to their purpose.

However, this pursuit can lead to emptiness, as power and gratification fail to provide lasting fulfillment. Antagonists often end up isolated, realizing that their selfishness and cruelty ultimately lead to their downfall, revealing the hollowness of their chosen path.

The antagonist’s hedonistic behavior, driven by self-indulgence and a disregard for the consequences, ultimately fuels chaos and destruction, hastening the end of the world they once sought to control.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the journey to find meaning in life is deeply intertwined with the experience of suffering and the ability to maintain nobility in the face of responsibility. The example of Jesus Christ teaches us that true growth and transformation often emerge from our willingness to endure hardship with grace and integrity.

By embracing our duties, confronting pain, and using it to create purpose, we can find profound meaning in our lives, just as Jesus did in his mission. Ultimately, it is through this balance of suffering, responsibility, and love that we shape our legacy and contribute to the greater good.

Creation and destruction are both essential for any meaningful narrative to unfold. Creation brings new possibilities and growth, while destruction clears the path for renewal. Together, they form a dynamic balance, where destruction makes space for new creation, and creation gives meaning to destruction. This interplay drives evolution, ensuring both growth and change are constantly present.

Is balancing these two universes and aspects of humanity the goal?

The ideal could indeed be about balancing these two visions—the material and the spiritual world. By integrating both, one can acknowledge the importance of the tangible, physical reality while also recognizing the deeper, transcendent aspects of existence.

The material world offers the opportunity to build, create, and engage in personal growth, while the spiritual world guides the pursuit of meaning, purpose, and connection to something greater than oneself. Achieving a balance between these realms allows for a holistic approach to life, where material success and spiritual fulfillment coexist, each enhancing the other.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings