We live in a world saturated with stories—some factual, others fictional, many floating somewhere in between. In an age obsessed with facts, we often forget that not all truths are literal, and not all fictions are lies. Some stories, though they never happened, still manage to reveal something deeply real—something that resonates beyond the surface of events.

This is the strange power of myth. Unlike a lie, which deceives, a myth speaks to the soul in a language older than logic. It carries symbolic truth, emotional resonance, and spiritual clarity. It’s the kind of story we don’t just hear—we live.

In Yann Martel’s Life of Pi, this distinction between lie and myth becomes the central question. What matters more: the brutal reality or the beautiful story? As we follow Pi’s journey across the ocean with a tiger named Richard Parker, we’re invited into a parable—not just about survival, but about how we hold onto meaning when reality breaks us.

This article dives into that distinction—Lie vs Myth—and explores why myth, though not always factually true, might be the truest thing we have.

A few words on Life of Pie

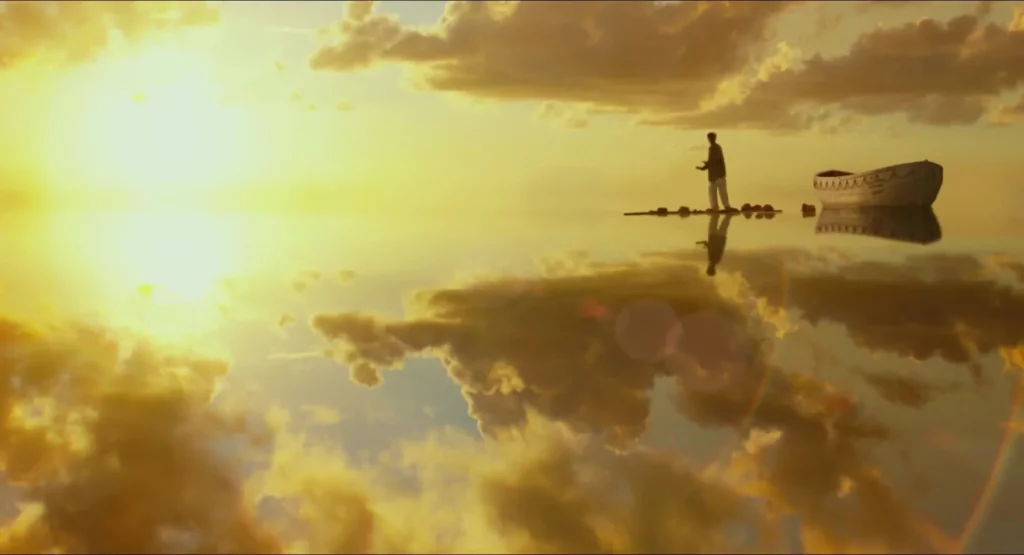

The film adaptation of Life of Pi, directed by Ang Lee famous for Brokeback Mountain and Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, released in 2012, elevates the book’s meditative narrative into a visually poetic experience.

Through breathtaking cinematography and symbolic imagery, the movie becomes not just a retelling of Pi’s journey, but a visceral exploration of myth, memory, and the human spirit.

The plot

Life of Pi follows Piscine Molitor Patel, a young Indian boy who survives a shipwreck and finds himself adrift in the Pacific Ocean — sharing a lifeboat with a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker. Over 227 days at sea, Pi faces hunger, trauma, and a spiritual journey, with the tiger becoming both a threat and a companion.

As an adult, Pi recounts his tale to a writer seeking a story that makes him believe in God. When asked for a more “realistic” version, Pi offers a darker, human-centered account. The film ends with a choice: between a brutal truth and a meaningful myth — asking which story we choose to believe, and what that says about us.

The metaphorical elements

In Life of Pi, especially in the movie adaptation, each animal in the lifeboat serves as an allegorical representation of a human character from the more brutal, “realistic” version of the story that Pi tells at the end. Here’s a breakdown of what each animal is believed to symbolize:

Richard Parker (The Bengal Tiger)

Represents: Pi himself — his primal instincts, survival drive, and inner darkness.

The tiger symbolizes the part of Pi that emerges to help him survive the unthinkable. It’s his shadow self, as Carl Jung would put it — dangerous, raw, yet essential. Richard Parker is not just a companion but also a metaphor for Pi’s suppressed violence and animalistic instincts that surface in extreme conditions.

The Orangutan (Orange Juice)

Represents: Pi’s mother

Orange Juice is gentle, nurturing, and mournful, just like a mother figure. Her maternal nature stands in contrast to the violence around her. Her brutal death in the hands of the hyena parallels the human version where Pi’s mother is killed in front of him.

The Hyena

Represents: The cook (played by Gérard Depardieu in the film)

The hyena is cruel, chaotic, and predatory. It reflects the cook’s selfishness, violence, and moral degradation after the shipwreck. In the realistic story, the cook murders Pi’s mother, showing a descent into savagery.

Just like the french cook, the hyena perfectly embodied evil — resourceful yet devoid of transcendence or spirituality, they represent a cold rationalism, disenchantment and brute savagery.

The Zebra

Represents: The sailor

The zebra is wounded early and suffers greatly, just like the sailor with a broken leg in the second version of the story. The zebra’s suffering represents innocence and helplessness in a brutal environment.

The Lifeboat

Itself is symbolic of the world, or even the mind — a limited space where Pi must negotiate between reason, instinct, emotion, and faith. The isolation and proximity to danger force a confrontation with self and God.

The Carnivore Island

The carnivorous island in Life of Pi represents spiritual stagnation disguised as safety — a false paradise where the body is fed, but the soul quietly withers. It offers Pi everything he needs to survive, yet without purpose, love, or transcendence.

Over time, the island reveals its true nature: comfort that turns toxic, abundance that devours, and stillness that leads to decay. Spiritually, it symbolizes the danger of choosing ease over meaning — a trap where one stops growing, stops seeking.

When Pi discovers the remains of a soul who stayed too long, he understands the deeper truth: survival without purpose is death in disguise, and the journey toward meaning must go on.

The carnivore island is a metaphor for the modern condition when we surrender completely to comfort, control, and convenience and forget transcendence, truth, and courage. This island represents the lie and its occupants denial.

The meerkats

The meerkats on the island can be seen as a metaphor for a society that appears safe, passive, and uniform — but ultimately lacks depth, individuality, or soul.

They’re everywhere, behaving in predictable patterns, going about their routines… yet completely unaware of the deeper danger lurking beneath the surface (the island becoming carnivorous at night). They represent what happens when a community becomes so fixated on safety and habit that it loses the instinct for truth, transcendence, or even survival.

To think – how many hours spent with only meerkats for company? How much loneliness taken on?

It’s a haunting metaphor for conformity, spiritual stagnation, and being alone in a crowd that no longer questions or seeks.

The themes

1. Faith vs. Reason

The central tension of the story: should we believe in the story with the tiger (faith), or the brutal one with humans (reason)? The film challenges us to see how myth can reveal truths that facts cannot.

2. The Power of Storytelling

Pi’s tale is a metaphor for how stories shape meaning. A good story isn’t just about what happened — it’s about how we process pain, beauty, and the unknown.

3. Survival and the Human Spirit

The journey at sea is both physical and psychological. Pi’s ability to endure trauma is deeply tied to his spiritual beliefs and imagination.

4. Duality of Human Nature

Richard Parker may represent Pi’s primal self — the raw instinct needed to survive. The film explores the coexistence of the divine and the animal within us.

5. Illusion and Truth

The movie suggests that truth isn’t always literal. Sometimes, illusion — or myth — is the only way to express spiritual or emotional truths.

6. Loneliness and Companionship

Pi’s relationship with the tiger shows how we project companionship onto others (even beasts or symbols) to stay sane and connected in isolation.

A Journey Between Survival, Story, and the Sacred

In Yann Martel’s Life of Pi, the protagonist Pi Patel survives a shipwreck and tells two radically different versions of his ordeal:

- A wondrous story involving a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker.

- A brutal, realistic story of survival, cannibalism, and human violence.

At the end of the book, Pi poses the question:

- “Which is the better story?”

- And the listener, a journalist, answers:

- “The one with the tiger.”

- And Pi responds:

- “And so it goes with God.”

This moment encapsulates the very heart of the Lie vs Myth distinction.

1. The “Tiger Story” as Myth

The version with Richard Parker—the animal allegory—is not literally true, but it’s mythologically rich. It carries symbolic weight:

- The tiger represents Pi’s primal survival instincts.

- The ocean is the unconscious, the spiritual abyss.

- The carnivorous island symbolizes temptation and spiritual stagnation.

- The blind encounter with another castaway reflects human isolation and the desperate search for meaning.

- Pi’s survival is not just about staying alive, but about preserving his soul.

This version is myth, not in the sense of being a falsehood, but in the Jungian sense: a symbolic narrative that tells a deeper truth. Pi chooses to preserve his humanity through story. The myth allows him to transcend trauma and integrate the unbearable into a meaningful whole.

2. The “Realistic Story” as Literal Truth — But a Possible Poison for the Soul

The second version is darker, factual, and void of magic. It may be more “realistic” in a factual sense—but it lacks redemptive power. It is stripped of the sacred. It may be true to the facts, but it is a poison to the spirit, because it leaves Pi broken, disenchanted, and dehumanized.

When truth is reduced to cold fact without meaning, it becomes indistinguishable from nihilism. We need stories that preserve our alignment with being, not just our memory of events.

In other words: a truth without meaning can be as damaging as a lie.

3. Story as Survival — of the Soul

Pi’s use of the tiger story is not escapism. It’s transformation. He isn’t lying to avoid reality. He is crafting a sacred myth to preserve the truth of his experience, without surrendering to despair.

This is the moral and spiritual function of myth. It doesn’t erase pain—it gives pain a structure that can be borne, remembered, and even cherished. That’s why when he says,

“And so it goes with God,”

he’s making a profound claim: God is not just the answer to what is factually true, but to what gives life meaning.

4. Lie vs Myth, Revisited in Pi’s Story

| Concept | Tiger Story (Myth) | Human Story (Literal/Brutal Truth) |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship to Truth | Symbolic, poetic, archetypal | Empirical, brutal, fact-based |

| Effect on the Soul | Redemptive, integrating, spiritual | Traumatizing, disintegrating, meaningless |

| Function | Preserves inner coherence and dignity | Reveals horror but offers no transcendence |

| Meaning | Truth through narrative | Truth at the cost of meaning |

5. The Deeper Message: The Power of Sacred Fiction

Life of Pi suggests that myth is not a lie we tell ourselves—it’s the story that keeps us alive. The book is an argument for the necessity of the sacred imagination in a world that often prizes raw fact over narrative depth.

Just like Carl Jung would say:

“People don’t have ideas. Ideas have people.”

We live inside our stories—so we better choose the ones that elevate our soul, not break it.

Why Mythology Is the History of Morality

Because myths don’t tell us what happened —they tell us what we need to understand in order to live with dignity.

They are a moral memory of humanity, encoded in symbols:

- The hero descending into the underworld (like Orpheus or Dante) = confronting one’s own shadow.

- The dragon to be slain = our fears, anger, and untamed impulses.

- The fire stolen from the gods (Prometheus) = the price of knowledge and responsibility.

- The return home (Odysseus) = the path of wisdom and forgiveness after trials.

Mythology: the theater of the soul

These are stories that are true on the inside, even if false on the outside.

They teach us how to be just, how to rise again, and how to sacrifice what must die in us in order to be reborn.

Without mythology?

- We have facts, but no meaning.

- We have intelligence, but no wisdom.

- We have the world, but no soul.

Every mythology is a moral education embodied in imagination.

A way for human beings not to lose themselves in the chaos.

The problem of the intellect alone, or Luciferian intellect

The idea that the intellect alone, cut off from the heart or soul, can be “Luciferian” comes largely from esoteric Christian traditions or thinkers like C.S. Lewis ou Solzhenitsyn. Here’s why:

Lucifer, in certain symbolic narratives (notably in Christian tradition or Dante’s Divine Comedy), represents the light of knowledge turned away from God — meaning the intellect that sees itself as self-sufficient. It’s not intelligence itself that is bad, but the proud intellect that seeks to dominate, explain, and control without wisdom or humility.

Some eat meat, some vegetarian. I do not expect us to agree about everything, but I would much rather have you believe in something I don’t agree with, than to accept everything blindly.

In this view:

- The Luciferian intellect wants to analyze, dissect, and reduce everything — even mystery, even the sacred.

- It rejects myth, intuition, and symbolism, because it cannot stand what it cannot prove.

- It replaces meaning with power, truth with technocracy, and soul with efficiency.

That’s why it’s said the Luciferian intellect can lead to moral or spiritual disintegration: it knows much, but understandsnothing. It shines a light, but does not guide.

In a sense, myth elevates, whereas the Luciferian intellect isolates. One seeks unity of being — the other seeks mastery of the world. On the other hand intellect is sometimes the first step into protecting ourselves against manipulation.

Differentiating myths and lies

A real myth speaks to the soul, not just the mind. It doesn’t exist to control or manipulate but to illuminate the human condition — helping us face fear, suffering, and transformation with meaning and dignity.

These myths echo across cultures and time because they address universal truths: the descent into darkness, the battle with inner demons, the return home wiser. They require us to grow, to sacrifice, to become more whole. In contrast, false myths are often comforting lies or ideological tools — created to justify power, sedate the masses, or avoid discomfort. They offer certainty instead of depth, obedience instead of introspection.

To distinguish the two, we must look inward. Ask yourself: does this story make me more courageous, more responsible, more attuned to something sacred? Or does it numb, divide, or simplify life into black and white? True myths call the soul to integrity; they awaken, rather than sedate. As Jung might say, a real myth doesn’t just tell you what happened — it tells you how to live in a world full of suffering, ambiguity, and awe. It doesn’t just preserve memory — it preserves meaning.

Conclusion: Between Fact and Meaning

The quote “All of life is an act of letting go, but what hurts the most is not taking a moment to say goodbye” means:

Throughout our lives, we constantly have to let go (faith)—of control, people, places, moments, even parts of ourselves. It’s a natural and inevitable part of living. However, the most painful experiences are often those where we didn’t get the chance to say goodbye—to bring closure, to express our feelings, to honor what’s being lost before it’s gone.

It’s about regret, the ache that comes not from the loss itself, but from the unfinished emotional business—things unsaid, gestures never made, endings that came too fast.

In the end, Life of Pi doesn’t ask, “Which story is true?” It asks,

“Which story makes life worth living?”

That’s the essence of myth. And that’s where the line between lie and myth becomes clear. A lie is a betrayal of what is. A myth is a vessel for what matters.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings