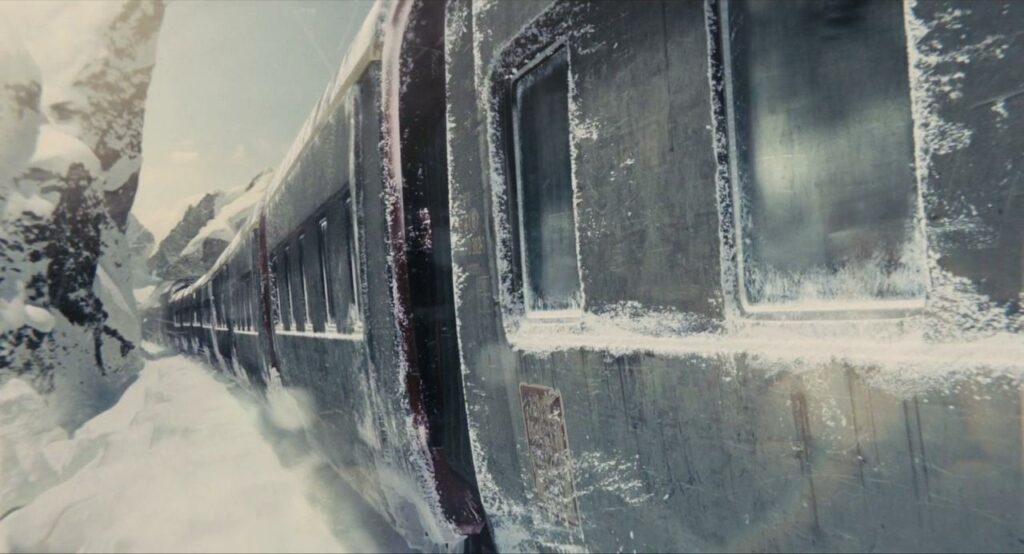

Snowpiercer, directed by Bong Joon-ho, is a dystopian sci-fi film that follows the journey of the last survivors of humanity on a perpetually moving train called the Snowpiercer. Set in a frozen, post-apocalyptic world, the film is both thrilling and profound, using the train as an allegory for societal structure, inequality, and class struggle.

As we analyze Snowpiercer and its symbolic elements, it becomes clear how closely its themes resonate with real-world dynamics, particularly concerning social hierarchies, systemic inequality, and the cost of sustaining rigid power structures.

Plot and Symbolism

In Snowpiercer, humanity’s last survivors are segregated by class within the train, which represents a microcosm of society. The lower-class passengers, forced to live in the cramped, dirty tail cars, subsist on protein blocks made from insects and live under strict control.

Meanwhile, the wealthier passengers at the front enjoy luxuries, high-quality food, and ample space. As the plot unfolds, the protagonist Curtis leads a revolt to reach the front, sparking a bloody journey that reveals the train’s social structure in all its bleak, oppressive reality.

Each car they pass through serves as a metaphor for different layers of social and economic privilege, with guards, high-quality food, classrooms, and leisure areas marking their ascent. The train, thus, becomes a powerful image of both literal and metaphorical divisions within society.

Key Themes and Real-World Parallels

1. Class Hierarchy and Inequality

The train’s rigid division into classes mirrors the economic disparity in the real world, where wealth and resources are concentrated at the “top” while the lower classes are forced to survive on limited resources.

In many ways, the social structure in Snowpiercer is similar to global economic inequality today, where the richest individuals and corporations hold vast amounts of wealth, leaving the lower economic strata struggling to survive.

The tail-end passengers live in appalling conditions and are told that this is their place in the “natural order” of the train’s ecosystem. Similarly, in the real world, many marginalized communities are told, either explicitly or implicitly, to accept their place within society.

Structural inequality is often justified by those in power as inevitable or necessary, fostering a self-sustaining cycle where the rich get richer, and the poor remain trapped in their circumstances.

2. Control and Ideology

Snowpiercer shows how those in power maintain control over the lower classes through a mix of fear, propaganda, and restriction. For instance, children in the middle cars are indoctrinated to believe in Wilford, the train’s creator and self-styled “engine god,” and are taught that the train is the only way to survive the apocalypse.

This education system symbolizes the ways in which ideologies can be used to pacify and control the masses, teaching them to accept their subservient role rather than challenging it.

In real life, control often comes through media, education, and laws that reinforce the status quo. Just as Wilford’s propaganda portrays the train’s hierarchy as essential to survival, modern narratives may portray systemic inequalities as inevitable or even beneficial.

This reinforces the power structure by preventing the lower classes from uniting or rising against the status quo.

3. Environmental Collapse and Class-Based Survival

The film’s apocalyptic setting was caused by a failed attempt to combat global warming, resulting in a frozen wasteland. This reflects real-world anxieties about climate change, environmental degradation, and the disproportionate impact these issues have on lower-income communities.

The wealthy passengers on Snowpiercer live in relative comfort, much like wealthier individuals in our world who can often evade the direct consequences of environmental crises by moving to safer areas, accessing resources, or utilizing new technology.

In the real world, marginalized communities are often the most affected by climate change. They face food insecurity, lack of shelter, and poor healthcare access, which are compounded by climate-related disasters.

The affluent, meanwhile, can afford adaptation measures, further widening the gap between classes. In Snowpiercer, this class-based survival is starkly highlighted: only those in the front of the train can maintain their quality of life, while the lower classes endure suffering with little chance of escape.

4. The Illusion of Progress and False Hope

The train’s circular journey, endlessly circling the frozen Earth, symbolizes the illusion of progress within an oppressive system. Curtis and his fellow rebels believe that reaching the front of the train will free them, only to discover that the system is cyclical and self-perpetuating.

Wilford even implies that the revolts themselves are necessary to maintain the balance of the train, suggesting that the rebellion was manipulated from the start to serve the interests of those in power.

This mirrors how social mobility in the real world can often feel like an illusion. While many people strive to break free from poverty, structural barriers often keep them from moving up, no matter how hard they fight. Revolutions, protests, and movements can be suppressed or co-opted to reinforce the current power dynamics.

By creating the illusion that progress is possible, those in power can prevent genuine structural change, much like Wilford uses controlled rebellion to maintain order.

5. Dehumanization and Survival at Any Cost

In Snowpiercer, dehumanization is starkly depicted in the treatment of the tail-end passengers, whose suffering is rationalized as a necessity for the train’s ecosystem. This reflects how marginalized groups are often dehumanized to justify inequality and exploitation.

In Curtis’s revelation about his past acts of cannibalism, we see how oppression can drive people to desperate measures for survival. Similarly, real-world poverty and marginalization can push people toward difficult or morally questionable decisions, often framed as survival tactics within an indifferent system.

The protein blocks made of insects, the squalor, and the indifference to suffering reflect the ways in which marginalized populations are treated as disposable. From sweatshop labor to refugee camps, this dehumanization allows societies to rationalize cruelty as a regrettable necessity.

Some accurate details

Egalitarian society and second amendment

The more a society embraces egalitarian principles, the more likely it is that people will have the right to bear arms as a means of maintaining a balance of power. Naturally, this doesn’t mean access to all types of weapons, but rather a level of armament sufficient to prevent tyranny from gaining a foothold.

In Snowpiercer, the imbalance of power is starkly evident in one of the train’s deadliest cars. Here, the guards — representing a type of police or military force — are heavily equipped, creating such a disparity that only a ceasefire prevents them from wiping out the working-class passengers entirely.

Industrial and insect food

In Snowpiercer, the passengers in the tail end of the train are given black gelatin blocks as food, which are later revealed to be made from cockroaches processed in the factory car further up the train.

Despite the abundance of fresh food that can be grown, hunted, or gathered in nature, people in modern society often consume pre-packaged, nutrient-poor, processed foods that are often made to reduce costs. Industrial are using cuts of meat that people would typically avoid, like parts of a cow that would otherwise go unused, sometimes worst.

These are combined with other inexpensive ingredients and end up in products like frozen burger patties. Now, there are even powdered foods like Huel, which appeal to those looking to avoid the hassle of cooking and save money.

Real life is found outside the train

In Snowpiercer, while life outside the train seems perilous and inhospitable, it represents the real, unfiltered world—something that the train’s insulated environment has suppressed. Inside the train, every aspect of life is controlled and manufactured to maintain a rigid system, limiting any sense of genuine freedom or growth.

Similarly, in the real world, many structures and routines created by society can feel like artificial constructs, offering stability and protection but often at the cost of true autonomy and exploration. Venturing beyond these constraints, while daunting, can lead to authentic experiences and a more profound understanding of one’s place in the world, just as stepping outside the train holds the possibility of real life beyond the confines of its system.

Tyranny is an endless cycle

Tyranny, as seen in both Snowpiercer and the historical cycle of oppression symbolized by Bastille Day in France, reveals itself as a seemingly endless loop where those in power suppress the masses to maintain control. In Snowpiercer, the strict social hierarchy on the train keeps the “tail-end” passengers under brutal conditions, with limited resources and no possibility for advancement. The front of the train, inhabited by the elite, enforces this order with extreme measures, creating an oppressive system that generates resentment and rebellion but continues to hold power tightly.

Similarly, in pre-revolutionary France, the monarchy imposed severe economic and social hardships on the lower classes, leading to inequality and widespread suffering. The storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, became a powerful symbol of the people’s uprising against oppressive forces. Much like the revolt within Snowpiercer, the French Revolution was a desperate push to break the cycle of tyranny, sparking a shift toward liberty and equality, even though it took years and many struggles to move towards meaningful change.

Both Snowpiercer and Bastille Day demonstrate that when power is unbalanced and concentrated among a privileged few, resentment builds until the oppressed reach a breaking point. Yet, in both scenarios, the cycles of control and resistance show how difficult it can be to break free of tyranny entirely. The fight may end in temporary triumph, but history suggests that new forms of authority often emerge to take the place of the old, as power and control seek to re-establish themselves in a different guise.

Opulence as a Tool of Control and Corruption

Snowpiercer uses the contrast between the stark living conditions in the tail cars and the lavish opulence of the front cars to critique excess and privilege. The passengers in the front of the train enjoy extravagant, almost absurd luxuries that seem entirely out of place in a world otherwise defined by survival. Scenes of people enjoying lavish meals, relaxing in spa-like settings, and indulging in high-end entertainment sharply juxtapose with the grim reality of those at the tail end, who are crammed into overcrowded, unsanitary conditions and fed a monotonous, insect-based diet.

The film suggests that opulence is not just an excess of resources but a deliberate mechanism of control. This opulence at the front isn’t necessary for survival; it exists as a show of power and to reinforce the social hierarchy that keeps the lower classes subordinated. The wealthier passengers’ access to beauty, fine dining, and luxurious settings—symbolized by colorful interiors and abundant foods—serves to maintain a psychological and physical barrier between them and the “working” class who suffer in hardship.

Moreover, Snowpiercer critiques how opulence can detach people from the realities and struggles of others. The front passengers are so insulated by their privilege that they seem numb or even blind to the plight of the tail-end passengers, reinforcing the idea that excess breeds apathy. Their ignorance or indifference to the conditions in the back cars underscores how extreme wealth can create moral blindness, allowing systems of oppression to persist unchallenged.

In a broader sense, Snowpiercer suggests that such opulence is ultimately destructive, both for individuals and for society. As the film progresses, the breakdown of order within the train serves as a warning against societies built on vast inequalities, where a small elite lives in wasteful excess while others suffer from manufactured scarcity. The film, therefore, portrays opulence not as a harmless luxury but as a dangerous, corrupting force that destabilizes and dehumanizes everyone involved.

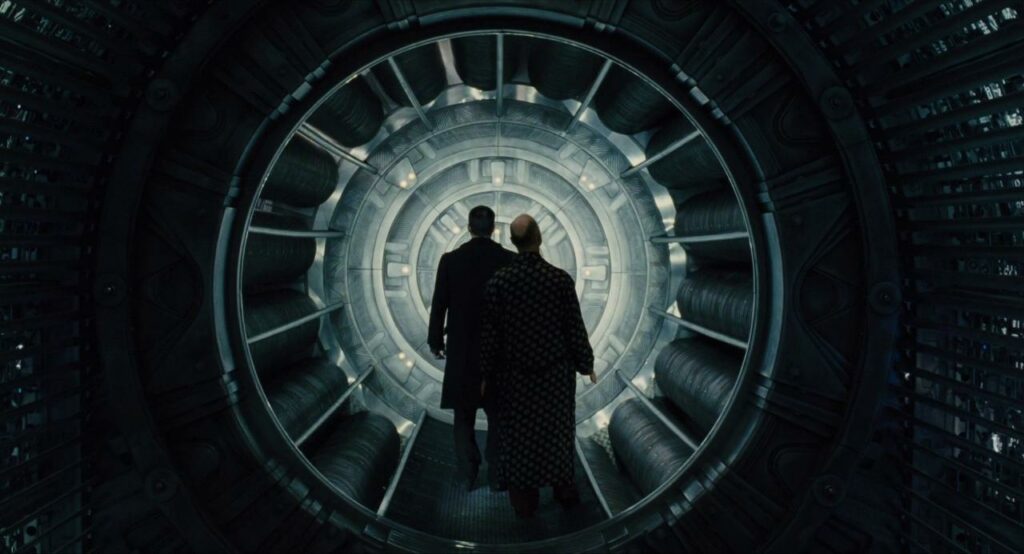

Necessary evil and controlled monster

In Snowpiercer, the dynamic between the antagonist Wilford and the protagonist Curtis illustrates the themes of necessary evil and the concept of a “controlled monster.” Wilford, the creator of the train and self-appointed authority, embodies a kind of “necessary evil” that justifies his control over the train’s population as the only way to sustain the system and prevent societal collapse.

Wilford’s approach to leadership is coldly logical; he designs an oppressive social order where suffering and sacrifice are vital to maintaining balance, even at the cost of human lives. He represents an intellectual playing with moral relativism—a figure who channels ruthlessness for a purpose, seeing his inhumanity as essential to sustaining life in a confined, chaotic environment.

Curtis, on the other hand, begins as a hero of the oppressed, a voice for justice. However, as he journeys through the train, he confronts the moral ambiguity of leadership and control, coming face to face with the harsh decisions required to maintain order. This journey exposes Curtis to the “necessary evil” required in Wilford’s world, forcing him to consider whether he too could become a necessary evil for the greater good.

By contrasting Curtis’s initial innocence with Wilford’s calculated cruelty, we later learn that Curtis himself harbors a dark past as a cannibal who once killed women and ate infants to survive, only to eventually be transformed by the influence and compassion of Gilliam which is how he became a controlled monster through faith and moral.

Snowpiercer raises the question of whether maintaining balance in an enclosed, survival-based world is possible without sacrificing humanity—or if every leader must ultimately grapple with the cruel side of control. It also reminds us that being a protagonist often requires harboring the same darkness found in the antagonist.

Conclusion: What Snowpiercer Says About Society

Snowpiercer offers a dark and cynical view of society, presenting a world where inequality is not only institutionalized but considered essential for the system’s survival.

It asks us to consider the structures we accept, the suffering they perpetuate, and the cost of preserving such systems. In the film, true liberation only comes when the train is destroyed, suggesting that dismantling entrenched systems may be necessary to break free from cycles of oppression.

In real life, the questions are similarly profound: Can we reform our institutions, or are they too deeply entrenched in inequality? Are there ways to create a more equitable society without dismantling established structures?

Snowpiercer forces us to confront the possibility that real change may require challenging the very foundations of our social, economic, and environmental systems. By drawing such close parallels to real life, Snowpiercer serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked power and the potential cost of maintaining a status quo that benefits the few at the expense of the many.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings